African Modernism 1 -Kenchikushi 10.2020

原文で表示 (日本語)Cover: Kampala Serena International Conference Center

During the 1950s and 1960s, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa achieved independence. Many people may know 1960 as the ‘Year of Africa’, when many countries in particular declared their independence at the same time.However, it is not widely known what kind of architecture was built in Africa during this period.

In his book AFRICAN MODERNISM, the German architect Manuel Herz summarises the major modernist buildings of Ghana, Senegal, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya and Zambia in the following way: “These buildings are examples of the world’s leading works of the 1960s and 1970s, yet they have not received the attention they deserve. There are still masterpieces to be discovered. (Author’s translation)” He notes that the Parliament buildings, the Central Bank, the stadiums, the conference halls, the universities, etc., demanded a bold expression of a modern and hopeful future, and asks whether unravelling the architecture of this period can help to reveal the process of decolonisation of the country. I would suggest otherwise. Architecture must have been an important means of expressing the identity of young nation in many countries that gained independence.

Uganda gained its independence on 9 October 1962, in line with other countries. Photographs taken in the then capital, Kampala, show that a large-scale project was underway to create a new post-independence architecture, making extensive use of technology and construction methods brought in from Europe. However, the political upheaval that made Idi Amin’s name known around the world between 1971 and 1979 was followed by the departure of many foreigners, including architects and engineers, during the period. Many of the drawings and other documents were destroyed, and many of the details of the architects, builders and the process of construction are no longer known.

National Theatre, 1959, Peatfield and Bodgener

National Theatre, 1959, Peatfield and Bodgener

There is now a movement to review the modernist architecture in Kampala in the wake of Manuel Hertz’s book. Doreen Adengo is a Ugandan architect who was educated in the US and returned to Uganda. As we joined the tour and listened to the stories, we looked at the buildings and realise the use of concrete, steel and glass. Though they were used in a straightforward manner, they were ingenious in dealing with the tropical climate and in connecting the interior and exterior spaces in search of a sense of ‘character’. In contrast to the impersonal glass-fronted buildings that have proliferated in Kampala in recent years (which she calls “Dubai-ism architecture”), an important movement has begun to raise awareness of its existence through tours, and eventually to preserve it.

For almost half a century, these masterpieces have undergone a unique transformation, changing their use and owners over time. What should be created here in the future? Or should it not be? I feel as if they are suggesting to us.

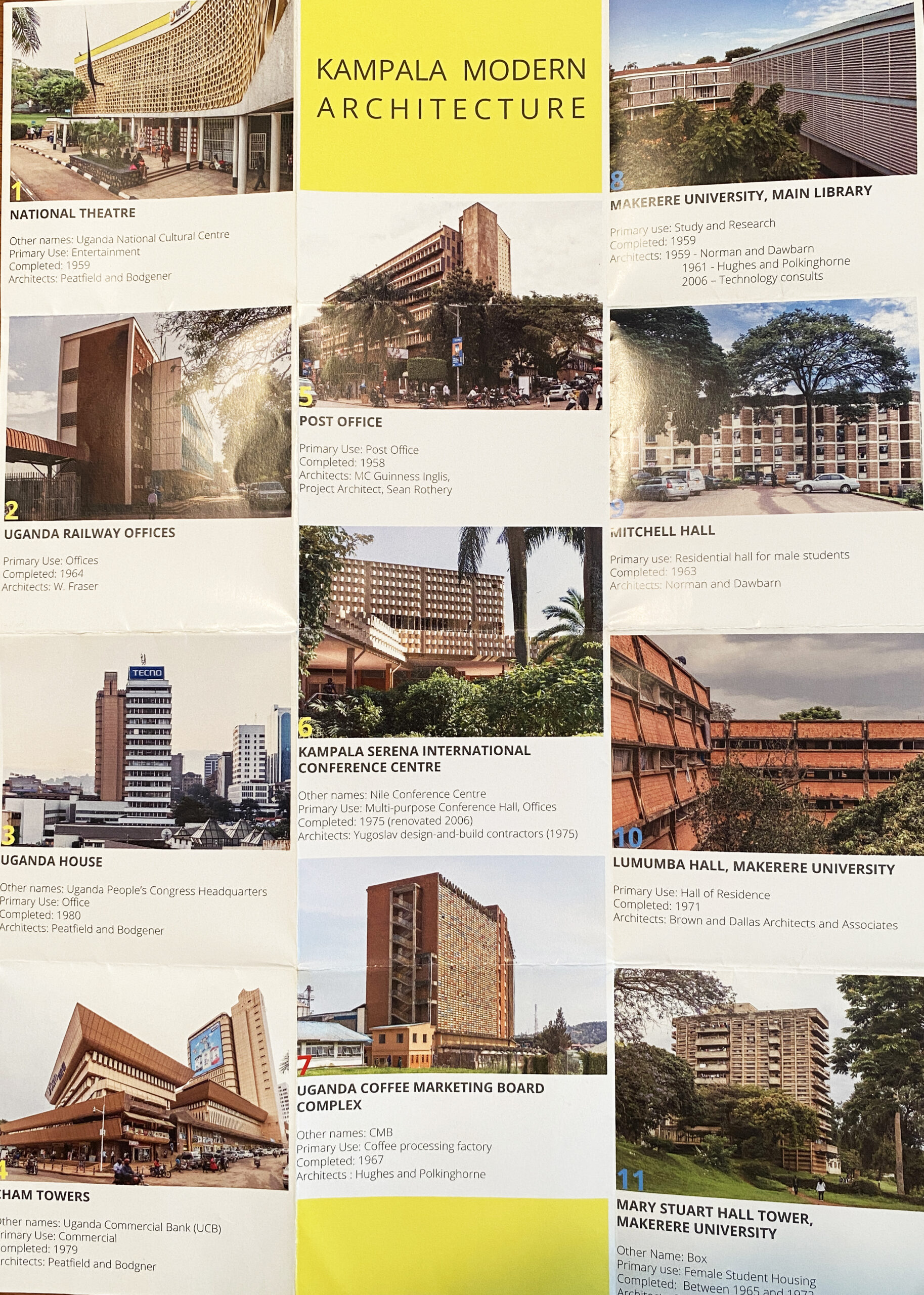

Kampala Modern Architecture Map (From Adengo Architecture)

Kampala Modern Architecture Map (From Adengo Architecture)

Photo : Ikko Kobayashi

Source : “Kenchikushi” Oct 2020